Coping Mechanisms: A Doctor’s Guide to Handling Life When It Gets Hard

“The greatest weapon against stress is our ability to choose one thought over another.”

— William James, philosopher and psychologist

We all face moments when life pushes us a little too far. Whether it’s the quiet, grinding pressure of daily responsibilities or the sharp blow of trauma or loss, stress is a part of the human experience. What matters most isn’t whether we face stress—but how we deal with it.

In medical terms, these responses are called coping mechanisms—the mental, emotional, and behavioral tools we use to handle discomfort, anxiety, sadness, fear, and overwhelm.

Some people vent to a friend, others go for a run. Some bury themselves in work. Others reach for a drink. Not all coping is created equal. Some strategies support long-term health and emotional regulation; others simply provide short-term escape.

This article is a deep dive into the world of coping—from the psychological frameworks to real-world applications, drawn from both clinical research and patient experiences.

What Exactly Is a Coping Mechanism?

A coping mechanism is any behavior, thought pattern, or action you use—consciously or unconsciously—to manage internal or external stressors. Coping helps you regulate your emotions, maintain functioning under pressure, and navigate complex or painful situations.

The concept has been a cornerstone in psychological research for decades. According to Lazarus and Folkman’s landmark transactional model of stress, coping is the process of managing demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person (Lazarus & Folkman, 1987).

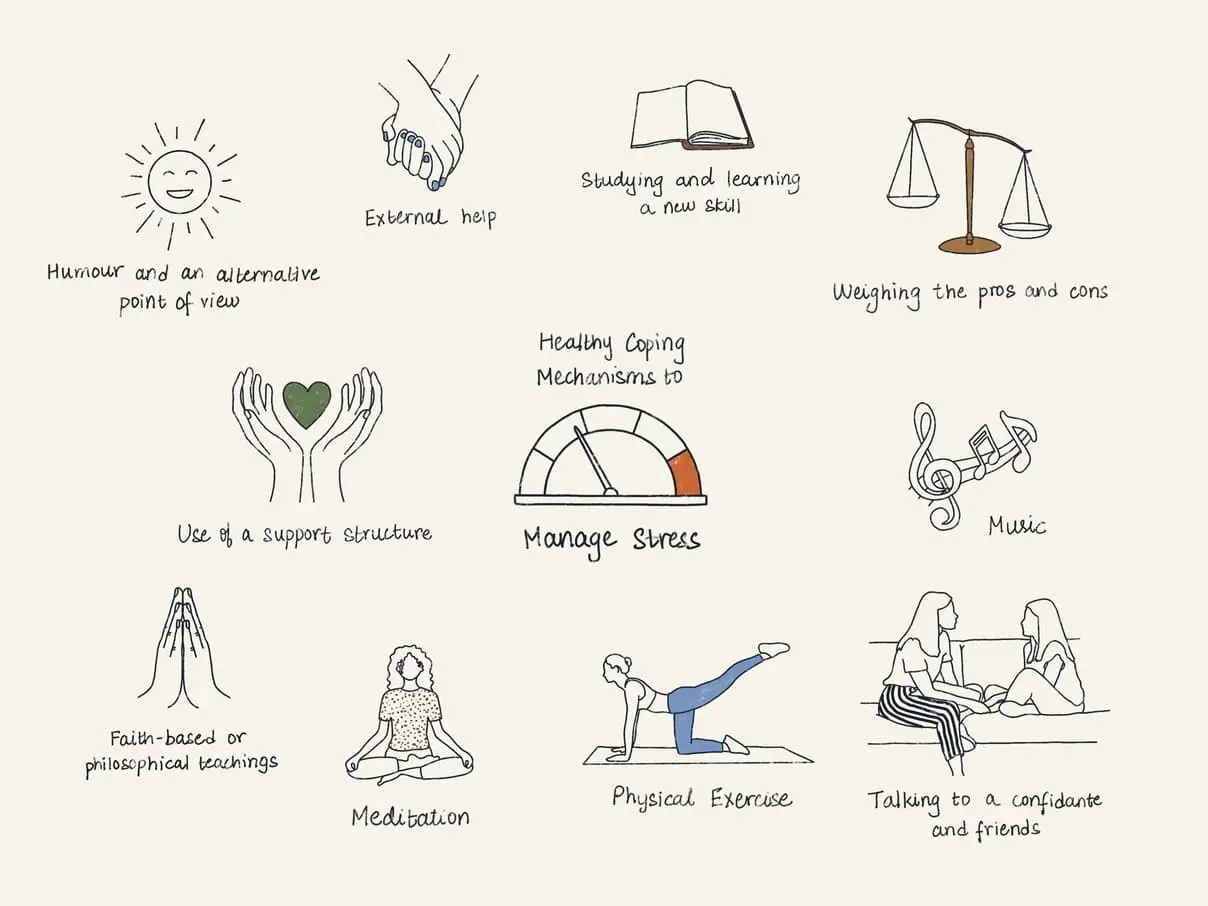

There are two primary dimensions:

Adaptive (Healthy) Coping: Constructive and sustainable responses that help reduce long-term stress or solve underlying problems.

Maladaptive (Unhealthy) Coping: Temporary fixes that may reduce distress in the moment but contribute to bigger problems over time.

Types of Coping Mechanisms

1. Problem-Focused Coping

This type of coping is aimed at resolving the actual stressor or minimizing its impact.

Examples include:

Creating a budget to manage financial stress.

Seeking legal help during a divorce.

Asking for accommodations at work or school.

🧠 Clinical Insight: Research shows that problem-focused coping tends to be most effective when individuals have some control over the situation. It provides a sense of agency and can reduce feelings of helplessness (Taylor, 2006).

2. Emotion-Focused Coping

This involves managing the emotional response rather than tackling the problem directly. It’s particularly useful when the situation is outside your control.

Healthy strategies include:

Practicing deep breathing, meditation, or yoga.

Talking to a therapist or trusted friend.

Reframing the situation with positive self-talk.

Unhealthy examples:

Binge eating or drinking.

Lashing out in anger.

Emotional withdrawal or denial.

“Sometimes, all you can do is control how you feel about what’s happening—even when you can’t change what’s happening.”

— Patient, age 47, PTSD survivor

3. Avoidance Coping (A Red Flag)

Avoidance coping can temporarily reduce distress, but it often worsens the problem in the long run. This includes denial, procrastination, and escapist behaviors like substance use or compulsive gaming.

Why it’s dangerous:

Prevents problem resolution.

Reinforces fear and helplessness.

Increases the risk of anxiety, depression, and addiction.

📚 According to a study published in Psychiatric Clinics of North America, avoidance behaviors are a strong predictor of chronic stress and poor mental health outcomes (NCBI, 2021).

4. Meaning-Making and Positive Reappraisal

This higher-level form of coping involves finding meaning or growth in adversity.

Examples:

Seeing a difficult breakup as an opportunity for self-discovery.

Using illness as a motivator to live more intentionally.

Transforming grief into advocacy or creative expression.

This approach is associated with resilience and post-traumatic growth. According to PositivePsychology.com, individuals who reframe stress in a constructive light often show better emotional regulation and recovery.

5. Social Support Coping

Never underestimate the power of human connection. Support from family, friends, or professionals can be a buffer against overwhelming stress.

Social coping includes:

Seeking advice from a peer.

Joining a grief support group.

Talking to a therapist or counselor.

“The moment I opened up to someone, everything shifted. I didn’t need them to fix anything—I just needed to be heard.”

— Sandra, age 62, caregiver

Healthy vs. Unhealthy Coping Mechanisms: Know the Difference

| Healthy Coping Strategies | Unhealthy Coping Strategies |

|---|---|

| Exercise, walking, yoga | Substance abuse (alcohol, drugs) |

| Mindfulness, breathing exercises | Emotional withdrawal, isolation |

| Journaling or creative expression | Overeating or restrictive eating |

| Talking to a therapist or friend | Excessive screen time, procrastination |

| Time management, goal-setting | Avoidance, denial, escapism |

| Humor and perspective-taking | Rage, aggression, blame-shifting |

🩺 Tip from clinical practice: Unhealthy coping isn’t a character flaw. It’s a signal. When people feel cornered and unsupported, they default to whatever dulls the pain fastest. The goal is to replace—not erase—those behaviors with something more sustainable.

Special Situations: Coping Mechanisms in Specific Populations

Teens and Young Adults

In younger patients, I often see emotional suppression, social withdrawal, or over-reliance on peers. Teaching proactive coping, emotional literacy, and healthy outlets like sports or music can be game-changing.

Older Adults

Retirement, grief, chronic illness—these stressors require a shift toward meaning-based coping and strong social support systems. Loneliness is a real public health concern in this group.

Chronic Illness Patients

Coping with chronic pain or disability demands a blend of problem-focused and acceptance-based strategies. “I stopped fighting the illness and started living with it,” one of my long-term patients with fibromyalgia once told me.

🧠 What the Research Says

A meta-analysis in the Journal of Behavioral Medicine showed that emotion-focused coping is helpful when stressors are uncontrollable (e.g., terminal illness), while problem-solving is more effective in solvable scenarios (Billings & Moos, 1981).

Gender plays a role: Studies suggest women are more likely to use emotion-focused coping and men lean toward problem-focused coping, though overlap is common.

According to the Cleveland Clinic, individuals who develop a toolkit of multiple coping skills are far more resilient than those relying on a single method.

🛠️ Building Your Own Coping Toolkit

Here’s a 3-step exercise I often give my patients:

Identify your current coping habits

What do you do when you’re stressed? Is it helping—or hurting?Audit and adjust

Replace one unhealthy habit with a healthier alternative each week.Build a “go-to” plan

Create a list of 3 strategies that help you calm down, 3 that give you energy, and 3 that help you feel supported.

🧾 Example:

Calm: Deep breathing, music, nature walk

Energy: Light jog, coffee with a friend, upbeat playlist

Support: Call mom, therapy session, journaling

You’re Not Alone, and You’re Not Broken

Coping is not a one-size-fits-all process—it’s a flexible, evolving skillset. Some days you’ll cope like a pro. Other days, you might just get through. That’s okay.

The goal isn’t to be perfect. It’s to recognize what you need and give yourself permission to meet those needs with compassion.

“You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.”

— Jon Kabat-Zinn